Private money, public parks

Council member Mark Levine wants to solve New York’s park equity problem. But before he can do that, he said, he needs to know just how deep the problem runs.

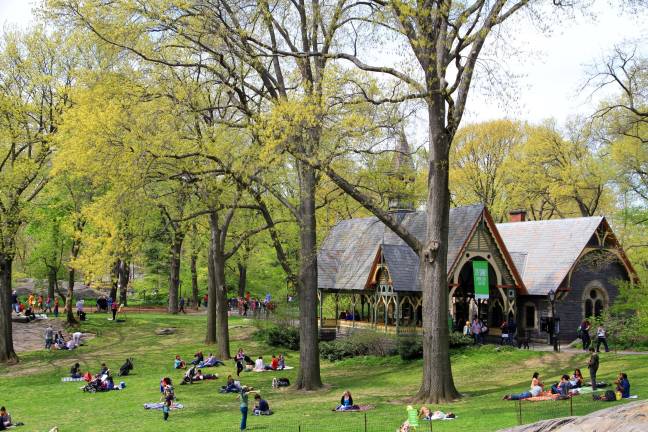

New York City has more than 1,700 parks, playgrounds and recreational facilities across the five boroughs. Of those, only a handful are well-funded and maintained by conservancies, which are private, non-profit organizations that enter into agreements with the parks department on the upkeep and programming of a particular public space.

The majority of parks, by contrast, are forced to make do with the department’s limited resources and backlog of work orders.

The disparity between these well-endowed parks and the less-affluent ones, especially in the outer boroughs, has led to a debate among urbanists, community advocates and elected officials about how the city’s resources, both private and public, should be distributed.

To that end, Levine recently introduced a bill that would require park conservancies to detail their revenue – much of it in the form of donations - and expenditures on an annual basis to the parks commissioner, who would create a report on all conservancies for the city council. The report will itemize monetary and material donations made by individuals and organizations to a particular conservancy, as well as how the conservancies allocate those resources.

Levine introduced a similar bill that would require the same disclosures of the parks department. Together, he said, they form the bedrock for identifying how vast the funding disparity is between the city’s parks and how the parks department allocates what money it has for maintenance and programming across its jurisdiction.

“I know what the parks department’s annual budget is,” said Levine, “but I can’t tell you how exactly they spend that money.”

Eventually, Levine said, the information will be used to put in place a plan that addresses the park equity problem.

“To really understand how big the gap is, we have to understand how much private money is going into parks and how much public money is going into the parks,” said Levine, who is chair of the council’s parks committee.

The bill concerning conservancies would affect organizations that enter into or renew an agreement with the parks department after July 1, 2015. Anonymous donors to conservancies would not be identified in the annual report, which would be released to the public every fall.

As non-profits, conservancies currently disclose this information, said Levine, but such disclosures are currently haphazard and sporadic. For instance, he said, park conservancies report this information on tax documents but in different cycles and sometimes up to 18 months after the period in question.

Levine said the bill isn’t aimed at any one conservancy, but “as a group, they have different fiscal years and they report on different cycles.”

The bill essentially brings into line conservancies’ fiscal reporting with the city’s budget schedule, “so we can start making apples to apples comparisons between public and private spending,” said Levine.

The Central Park Conservancy, easily the most high-profile and well-funded of the city’s private park conservancies, declined to comment on the bill “other than to say that we support it,” said a conservancy spokesperson.

Friends of the High Line testified at the parks committee hearing in support of Levine’s bill, and the Central Park Conservancy has made comments to the press in support of the bill, according to Levine.

“I’ve been really pleased to hear reports that conservancies are on board with this, are not opposed, and are all pledging to comply,” he said.

Levine said the conservancy bill was laid over for further discussion by the committee.