Ben Ostrer’s life of generous tenacity

Chester. Ben Ostrer was compelled by family conflicts with the legal system to become a lawyer who could wield the law with wisdom, assisting many without money along the way in difficult cases. He died at 71 on July 13.

Attorney Benjamin Ostrer, of Chester, who died at 71 on July 13, left behind a memorable trail of bold, sometimes controversial criminal and civil litigation that included abundant pro bono work.

“The frequency with which we convict innocent people should be shocking to everyone, and a call to legislators [to change our laws].” Ostrer said. “For everyone exonerated, there are an untold number of innocent people who are never exonerated.”

He was one of the foremost criminal defense attorneys in the Hudson Valley and had a reputation for obtaining acquittals in complex murder cases.

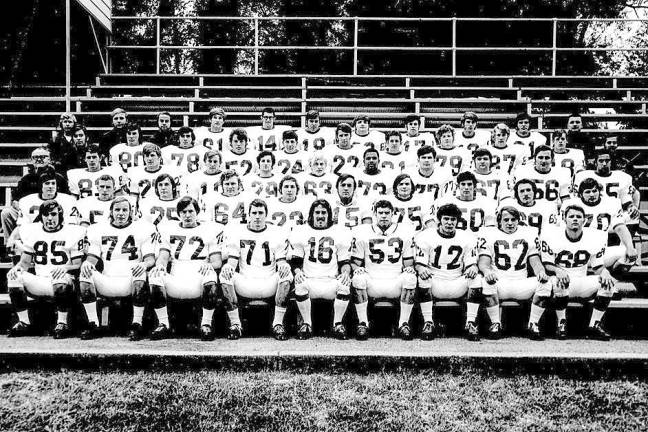

Born in Brooklyn in 1951, to Louis and Rita Ostrer, Ben Ostrer and his brothers grew up in Great Neck, L.I. He graduated with a degree in history from Alfred University in 1973, where he was a linebacker for an undefeated Lambert Bowl-winning Alfred University football team. Later Ben and his brother Steve, who had a degree in Agriculture from Cornell University, moved to Chester and owned Chester Valley Horse Farm on Pine Hill Road in Sugar Loaf for 19 years. Ben and Steve had a sales office, Ostrer Brothers, in Elmhurst, Queens, near Belmont racetrack.

While living on the farm, Ben commuted to law school his last year. He received his law degree from New York Law School in 1976 and was admitted to the bar in 1977. He practiced law part-time and in 1986 started his law practice.

Ostrer expected the advent of DNA tracing to reduce wrongful convictions. However, he said, “Labs get things wrong--and that’s with people who are fortunate enough to have forensic evidence.”

In an interview with The Chronicle in 2016, Ostrer mentioned several areas of law that needed reform. One was criminal records. He wanted expungement made accessible, so people could clear their record of a criminal conviction. Lack of expungement law disproportionately affected the minority community, he said.

“Know how many people’s lives were ruined with marijuana convictions?” he asked rhetorically. New York now has expungement.

Another realm that troubled Ostrer was the “discovery process.” At the time Ostrer was interviewed, a district attorney could have information he was not required to provide the defense until a jury was selected or already hearing the case. Ostrer argued for a fair playing field.

Under a new 2019 law, the prosecution must provide the defense with all evidence available to them within 15 days of an arraignment, with some exceptions.

Ostrer also wanted to see the age raised at which children were prosecuted as adults from 16 to 18. In 2016, New York was one of only two states that prosecuted 16 year-olds as adults.

“We now know from science that a young person’s brain is not fully developed at that age, and they should not be prosecuted as adults,” he said. The age is now 18.

Evan Ostrer remembers his father

Ben’s son Evan, now a lawyer in New Jersey, had the opportunity to work with his father, including on the shaken baby homicide case in Ulster. When police went to the scene, the defendant said the baby fell off the bed, and he shook the baby to see if he was okay.

“The police seized on ‘shook the baby.’ But there were injuries to the baby’s head that were consistent with the fall,” Evan Ostrer said. “A defense expert said the head trauma was consistent with falling off the bed. My dad’s cross examination was the turning point. The expert testimony was icing on the cake.”

Evan noted his father’s diligence.

“He won what most lawyers would think were unwinnable cases. He made his living defending the defenseless. If there was science involved, my father would study so much he was a worthy adversary to the prosecution’s expert witness.”

That diligence was also applied to pro bono work.

“He did pro bono work for a number of clients where he spent years working for free. He’d see cases to the bitter end. He was like that in his private life. Seeing things through and always there to help.”

Ostrer’s practice also included personal injury and appellate cases.

Additionally, he served as first vice chairman of the county GOP committee, and he was a former chairman of the Town of Chester Republican Committee. When he wasn’t practicing law, Ostrer liked to spend time with his family, reading and gardening.

In 2016, he received the Charles F. Crimi Memorial Award as the Outstanding Private Criminal Defense Attorney in New York State from the New York State Bar Association The bar association later honored Ostrer with its Outstanding Volunteer of the Year Award, recognizing his pro bono work. In 2022, the N.Y.S. Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers gave him its Lifetime Achievement Award for dedicated service to the profession.

What brought him in to criminal law was a family circumstance; he saw injustice and wanted to fight it. - Orange County District Attorney David Hoovler