Deja vu

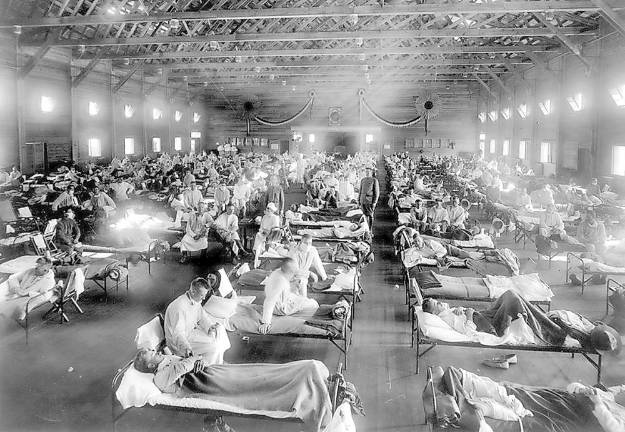

Spanish Flu: The Influenza epidemic in the United States 1918-1919.

The “Spanish flu” pandemic struck with lethal force in 1918 and infected an estimated 500 million people worldwide, about one-third of the world’s population, and killed an estimated 20 million to 50 million victims, including some 675,000 Americans.

Estimates vary, with some stating 100 million died, but exact figures are unknown because adequate records were not kept in many places.

After being weakened by influenza, most died from a secondary infection of pneumonia. A strong response mounted by an individual’s own immune system made things worse by increasing inflammation in the lungs.

At the time, there were no effective drugs or vaccines to treat this killer flu strain. Citizens were ordered to wear masks, schools, theaters and businesses were shuttered and bodies piled up in makeshift morgues before the highly contagious virus ended its deadly global march. Interestingly, schools were not closed in New York City, but school nurses would send home any sick child.

After several ships arrived from Europe carrying infected returning troops, passengers and sailors, New York City Health Commissioner Dr. Royal S. Copeland placed the entire Port of New York under quarantine on Sept. 12. Influenza was added to the list of reportable diseases, requiring all cases to be isolated. Business were ordered to open and close at staggered hours to avoid overcrowding on the subways.

Examination rooms were established at Pennsylvania and Grand Central stations, where all passengers who arrived feeling ill were examined by doctors and nurses. Those found to be suffering from influenza were sent to a hospital or put in the care of friends and not allowed to continue on public transportation.

An earlier, mild version of the flu had struck in the spring of 1918, but the second, deadliest and highly contagious wave of influenza appeared in the fall of that same year. A third wave occurred during the winter and spring of 1919. Victims died within hours or days of developing symptoms, their skin turning blue and their lungs filling with fluid that caused them to suffocate. The particular strain of influenza that caused the pandemic was first observed in Europe, America and parts of Asia before spreading to almost every other part of the world within months.

More U.S. soldiers died from the 1918 flu than were killed in battle during the war. By the War Department's most conservative count, influenza sickened 26 percent of the Army — more than one million men — and killed almost 30,000 before they even got to France. Troops moving around the world in crowded ships and trains helped to spread the virus. The confined conditions of training and staging camps, as well as of trench warfare, spread contagion. The war effort suffered because thousands of troops became unfit for duty.

Both the Allies and the Axis powers were greatly affected, but both sides did not publicize the information, wary of exposing any weakness and giving encouragement to their enemies.

Officials in some communities imposed quarantines, ordered citizens to wear masks and shut down public places, including schools, churches and theaters. People were advised to avoid shaking hands and to stay indoors, libraries stopped lending books and regulations were passed banning spitting.

The flu took a heavy human toll, wiping out entire families and leaving widows and orphans in its wake. Funeral parlors were overwhelmed and bodies piled up. Many people had to dig graves for their own family members.

The economy suffered. Businesses were forced to shut down because so many employees were sick. Basic services such as mail delivery and garbage collection were hampered due to flu-stricken workers.

In some places there weren’t enough farm workers to harvest crops. Even state and local health departments closed for business, hindering efforts to publicize the spread of the 1918 flu and provide the public with information about it.

In 1919, there was a milder strain of flu and by summer, the pandemic officially came to an end. Those who were infected either died or developed immunity.

Although some still search for the cause, in 2008, researchers announced they’d discovered what made the 1918 flu so deadly: A group of three genes enabled the virus to weaken a victim’s bronchial tubes and lungs and clear the way for bacterial pneumonia.

Despite the fact that the 1918 flu wasn’t isolated to one place, it became known around the world as the Spanish flu, as neutral Spain was devastated by the disease and, not subject to the wartime news blackouts that affected other countries, was the first country to publicize the pandemic.

In fact, the geographic origin of the flu is debated to this day, though hypotheses have suggested Europe, East Asia, and even Kansas.